Extremal principles in non-equilibrium thermodynamics

Energy dissipation and entropy production extremal principles are ideas developed within non-equilibrium thermodynamics that attempt to predict the likely steady states and dynamical structures that a physical system might show. The search for extremum principles for non-equilibrium thermodynamics follows their successful use in other branches of physics[1][2][3][4][5][6]. According to Kondepudi (2008)[7], and to Grandy (2008)[8], there is no general rule that provides an extremum principle that governs the evolution of a far-from-equilibrium system to a steady state. According to Glansdorff and Prigogine (1971, page 16)[9], irreversible processes usually are not governed by global extremal principles because description of their evolution requires differential equations which are not self-adjoint, but local extremal principles can be used for local solutions. Lebon Jou and Casas-Vásquez (2008)[10] state that "In non-equilibrium ... it is generally not possible to construct thermodynamic potentials depending on the whole set of variables". Šilhavý (1997)[11] offers the opinion that "... the extremum principles of thermodynamics ... do not have any counterpart for [non-equilibrium] steady states (despite many claims in the literature)." It follows that any general extremal principle for a non-equilibrium problem will need to refer in some detail to the constraints that are specific for the structure of the system considered in the problem.

Contents |

Fluctuations, entropy, 'thermodynamics forces', and reproducible dynamical structure

Apparent 'fluctuations', which appear to arise when initial conditions are inexactly specified, are the drivers of the formation of non-equilibrium dynamical structures. There is no special force of nature involved in the generation of such fluctuations. Exact specification of initial conditions would require statements of the positions and velocities of all particles in the system, obviously not a remotely practical possibility for a macroscopic system. This is the nature of thermodynamic fluctuations. They cannot be predicted in particular by the scientist, but they are determined by the laws of nature and they are the singular causes of the natural development of dynamical structure[9].

It is pointed out[12][13][14][15] by W.T. Grandy Jr that entropy, though it may be defined for a non-equilibrium system, is when strictly considered, only a macroscopic quantity that refers to the whole system, and is not a dynamical variable and in general does not act as a local potential that describes local physical forces. Under special circumstances, however, one can metaphorically think as if the thermal variables behaved like local physical forces. The approximation that constitutes classical irreversible thermodynamics is built on this metaphoric thinking.

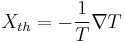

As indicated by the " " marks of Onsager (1931)[1], such a metaphorical but not categorically mechanical force, the thermal "force",  , 'drives' the conduction of heat. For this so-called "thermodynamic force", we can write

, 'drives' the conduction of heat. For this so-called "thermodynamic force", we can write

-

-

-

-

.

.

-

-

-

Actually this thermal "thermodynamic force" is a manifestation of the degree of inexact specification of the microscopic initial conditions for the system, expressed in the thermodynamic variable known as temperature,  . Temperature is only one example, and all the thermodynamic macroscopic variables constitute inexact specifications of the initial conditions, and have their respective "thermodynamic forces". These inexactitudes of specification are the source of the apparent fluctuations that drive the generation of dynamical structure, of the very precise but still less than perfect reproducibility of non-equilibrium experiments, and of the place of entropy in thermodynamics. If one did not know of such inexactitude of specification, one might find the origin of the fluctuations mysterious. What is meant here by "inexactitude of specification" is not that the mean values of the macroscopic variables are inexactly specified, but that the use of macroscopic variables to describe processes that actually occur by the motions and interactions of microscopic objects such as molecules is necessarily lacking in the molecular detail of the processes, and is thus inexact. There are many microscopic states compatible with a single macroscopic state, but only the latter is specified, and that is specified exactly for the purposes of the theory.

. Temperature is only one example, and all the thermodynamic macroscopic variables constitute inexact specifications of the initial conditions, and have their respective "thermodynamic forces". These inexactitudes of specification are the source of the apparent fluctuations that drive the generation of dynamical structure, of the very precise but still less than perfect reproducibility of non-equilibrium experiments, and of the place of entropy in thermodynamics. If one did not know of such inexactitude of specification, one might find the origin of the fluctuations mysterious. What is meant here by "inexactitude of specification" is not that the mean values of the macroscopic variables are inexactly specified, but that the use of macroscopic variables to describe processes that actually occur by the motions and interactions of microscopic objects such as molecules is necessarily lacking in the molecular detail of the processes, and is thus inexact. There are many microscopic states compatible with a single macroscopic state, but only the latter is specified, and that is specified exactly for the purposes of the theory.

It is reproducibility in repeated observations that identifies dynamical structure in a system. E.T. Jaynes[16][17][18][19] explains how this reproducibility is why entropy is so important in this topic: entropy is a measure of experimental reproducibility. The entropy tells how many times one would have to repeat the experiment in order to expect to see a departure from the usual reproducible result. When the process goes on in a system with less than a 'practically infinite' number (much much less than Avogadro's or Loschmidt's numbers) of molecules, the thermodynamic reproducibility fades, and fluctuations become easier to see[20][21].

According to this view of Jaynes, it is a common and mystificatory abuse of language, that one often sees reproducibility of dynamical structure called "order"[8][22]. Dewar[22] writes "Jaynes considered reproducibility - rather than disorder - to be the key idea behind the second law of thermodynamics (Jaynes 1963[23], 1965[19], 1988[24], 1989[25])." Grandy (2008)[8] in section 4.3 on page 55 clarifies the distinction between the idea that entropy is related to order (which he considers to be an "unfortunate" "mischaracterization" that needs "debunking"), and the aforementioned idea of Jaynes that entropy is a measure of experimental reproducibility of process (which Grandy regards as correct). According to this view, even the admirable book of Glansdorff and Prigogine (1971)[9] is guilty of this unfortunate abuse of language.

Local thermodynamic equilibrium

Various principles have been proposed by diverse authors for over a century. According to Glansdorff and Prigogine (1971, page 15)[9], in general, these principles apply only to systems that can be described by thermodynamical variables, in which dissipative processes dominate by excluding large deviations from statistical equilibrium. The thermodynamical variables are defined subject the kinematical requirement of local thermodynamic equilibrium. This means that collisions between molecules are so frequent that chemical and radiative processes do not disrupt the local Maxwell-Boltzmann distribution of molecular velocities.

Linear and non-linear processes

Dissipative structures can depend on the presence of non-linearity in their dynamical régimes. Autocatalytic reactions provide examples of non-linear dynamics, and may lead to the natural evolution of self-organised dissipative structures.

Continuous and Discontinuous Motions of Fluids

Much of the theory of classical non-equilibrium thermodynamics is concerned with the spatially continuous motion of fluids, but fluids can also move with spatial discontinuities. Helmholtz (1868)[26] wrote about how in a flowing fluid, there can arise a zero fluid pressure, which sees the fluid broken asunder. This arises from the momentum of the fluid flow, showing a different kind of dynamical structure from that of the conduction of heat or electricity. Thus for example: water from a nozzle can form a shower of droplets (Rayleigh 1878[27], and in section 357 et seq. of Rayleigh (1896/1926)[28]); waves on the surface of the sea break discontinuously when they reach the shore (Thom 1975[29]). Helmholtz pointed out that the sounds of organ pipes must arise from such discontinuity of flow, occasioned by the passage of air past a sharp-edged obstacle; otherwise the oscillatory character of the sound wave would be damped away to nothing. The definition of the rate of entropy production of such a flow is not covered by the usual theory of classical non-equilibrium thermodynamics. There are many other commonly observed discontinuities of fluid flow that also lie beyond the scope of the classical theory of non-equilibrium thermodynamics, such as: bubbles in boiling liquids and in effervescent drinks; protected towers of deep tropical convection (Riehl, Malkus 1958[30]), also called penetrative convection (Lindzen 1977[31]).

Historical development

W. Thomson, Baron Kelvin

William Thompson, later Baron Kelvin, (1852 a[32], 1852 b[33]) wrote

"II. When heat is created by any unreversible process (such as friction), there is a dissipation of mechanical energy, and a full restoration of it to its primitive condition is impossible.

III. When heat is diffused by conduction, there is a dissipation of mechanical energy, and perfect restoration is impossible.

IV. When radiant heat or light is absorbed, otherwise than in vegetation, or in a chemical reaction, there is a dissipation of mechanical energy, and perfect restoration is impossible."

In 1854, Thompson wrote about the relation between two previously known non-equilibrium effects. In the Peltier effect, an electric current driven by an external electric field across a bimetallic junction will cause heat to be carried across the junction when the temperature gradient is constrained to zero. In the Seebeck effect, a flow of heat driven by a temperature gradient across such a junction will cause an electromotive force across the junction when the electric current is constrained to zero. Thus thermal and electric effects are said to be coupled. Thompson (1854)[34] proposed a theoretical argument, partly based on the work of Carnot and Clausius, and in those days partly simply speculative, that the coupling constants of these two effects would be found experimentally to be equal. Experiment later confirmed this proposal. It was later one of the ideas that led Onsager to his results as noted below.

Helmholtz

In 1869, Hermann von Helmholtz stated[35], subject to a certain kind of boundary condition, a principle of least viscous dissipation of kinetic energy: "For a steady flow in a viscous liquid, with the speeds of flow on the boundaries of the fluid being given steady, in the limit of small speeds, the currents in the liquid so distribute themselves that the dissipation of kinetic energy by friction is minimum."[36]

In 1878, Helmholtz[37], like Thomson also citing Carnot and Clausius, wrote about electric current in an electrolyte solution with a concentration gradient. This shows a non-equilibrium coupling, between electric effects and concentration-driven diffusion. Like Thomson (Kelvin) as noted above, Helmholtz also found a reciprocal relation, and this was another of the ideas noted by Onsager.

J.W. Strutt, Baron Rayleigh

Rayleigh (1873)[38] (and in Sections 81 and 345 of Rayleigh (1896/1926)[28]) introduced the dissipation function for the description of dissipative processes involving viscosity. More general versions of this function have been used by many subsequent investigators of the nature of dissipative processes and dynamical structures. Rayleigh's dissipation function was conceived of from a mechanical viewpoint, and it did not refer in its definition to temperature, and it needed to be 'generalized' to make a dissipation function suitable for use in non-equilibrium thermodynamics.

Studying jets of water from a nozzle, Rayleigh (1878[27], 1896/1926[28]) noted that when a jet is in a state of conditionally stable dynamical structure, the mode of fluctuation most likely to grow to its full extent and lead to another state of conditionally stable dynamical structure is the one with the fastest growth rate. In other words, a jet can settle into a conditionally stable state, but it is likely to suffer fluctuation so as to pass to another, less unstable, conditionally stable state. He used like reasoning in a study of Bénard convection[39]. These physically lucid considerations of Rayleigh seem to contain the heart of the distinction between the principles of minimum and maximum rates of dissipation of energy and entropy production, which have been developed in the course of physical investigations by later authors.

Korteweg

Korteweg (1883)[40] gave a proof "that in any simply connected region, when the velocities along the boundaries are given, there exists, as far as the squares and products of the velocities may be neglected, only one solution of the equations for the steady motion of an incompressible viscous fluid, and that this solution is always stable." He attributed the first part of this theorem to Helmholtz, who had shown that it is a simple consequence of a theorem that "if the motion be steady, the currents in a viscous [incompressible] fluid are so distributed that the loss of [kinetic] energy due to viscosity is a minimum, on the supposition that the velocities along boundaries of the fluid are given." Because of the restriction to cases in which the squares and products of the velocities can be neglected, these motions are below the threshold for turbulence.

Onsager

Great theoretical progress was made by Onsager in 1931[1][41] and in 1953[42][43].

Prigogine

Further progress was made by Prigogine in 1945[44] and later[9][45]. Prigogine (1947)[44] cites Onsager (1931)[1][41].

Casimir

Casimir (1945)[46] extended the theory of Onsager.

Ziman

Ziman (1956)[47] gave very readable account. He proposed the following as a general principle of the thermodynamics of irreversible processes: "Consider all distributions of currents such that the intrinsic entropy production equals the extrinsic entropy production for the given set of forces. Then, of all current distributions satisfying this condition, the steady state distribution makes the entropy production a maximum." He commented that this was a known general principle, discovered by Onsager, but was "not quoted in any of the books on the subject". He notes the difference between this principle and "Prigogine's theorem, which states, crudely speaking, that if not all the forces acting on a system are fixed the free forces will take such values as to make the entropy production a minimum." Prigogine was present when this paper was read and he is reported by the journal editor to have given "notice that he doubted the validity of part of Ziman's thermodynamic interpretation".

Ziegler

Hans Ziegler extended the Melan-Prager's non-equilibrum theory of materials to the non-isothermal case [48].

Gyarmati

Gyarmati (1967/1970)[2] gives a systematic presentation, and extends Onsager's principle of least dissipation of energy, to give a more symmetric form known as Gyarmati's principle. Gyarmati (1967/1970)[2] cites 11 papers or books authored or co-authored by Prigogine.

Gyarmati (1967/1970)[2] also gives in Section III 5 a very helpful precis of the subtleties of Casimir (1945))[46]. He explains that the Onsager reciprocal relations concern variables which are even functions of the velocities of the molecules, and notes that Casimir went on to derive anti-symmetric relations concerning variables which are odd functions of the velocities of the molecules.

Paltridge

The physics of the earth's atmosphere includes dramatic events like lightning and the effects of volcanic eruptions, with discontinuities of motion such as noted by Helmholtz (1868)[26]. Turbulence is prominent in atmospheric convection. Other discontinuities include the formation of raindrops, hailstones, and snowflakes. The usual theory of classical non-equilibrium thermodynamics will need some extension to cover atmospheric physics. According to Tuck (2008)[49], "On the macroscopic level, the way has been pioneered by a meteorologist (Paltridge 1975[50], 2001[51]). Initially Paltridge (1975)[50] used the terminology "minimum entropy exchange", but after that, for example in Paltridge (1978)[52], and in Paltridge (1979)[53]), he used the now current terminology "maximum entropy production" to describe the same thing. This point is clarified in the review by Ozawa, Ohmura, Lorenz, Pujol (2003)[54]. Paltridge (1978)[52] cited Busse's (1967)[55] fluid mechanical work concerning an extremum principle. Nicolis and Nicolis (1980) [56] discuss Paltridge's work, and they comment that the behaviour of the entropy production is far from simple and universal. This seems natural in the context of the requirement of some classical theory of non-equilibrium thermodynamics that the threshold of turbulence not be crossed. Paltridge himself nowadays tends to prefer to think in terms of the dissipation function rather than in terms of rate of entropy production.

References

- ^ a b c d Onsager, L. (1931). Reciprocal relations in irreversible processes, I, Physical Review 37:405-426

- ^ a b c d Gyarmati, I. (1970). Non-equilibrium Thermodynamics. Field Theory and Variational Principles, Springer, Berlin.

- ^ Ziegler, H., (1983). An Introduction to Thermomechanics, North-Holland, Amsterdam, ISBN 0444865039

- ^ Martyushev, L.M., Seleznev, V.D. (2006). Maximum entropy production principle in physics, chemistry and biology, Physics Reports 426: 1-45

- ^ Martyushev, I.M., Nazarova, A.S., Seleznev, V.D. (2007). On the problem of the minimum entropy production in the nonequilibrium stationary state, Journal of Physics A: Mathematical and Theoretical 40: 371-380.

- ^ Hillert, M., Agren, J. (2006). Extremum principles for irreversible processes, Acta Materialia 54: 2063-2066.

- ^ Kondepudi, D. (2008)., Introduction to Modern Thermodynamics, Wiley, Chichester UK, ISBN 978-0-470-01598-8, page 172.

- ^ a b c Grandy, W.T., Jr (2008). Entropy and the Time Evolution of Macroscopic Systems, Oxford University Press, Oxford, ISBN 9780199546176.

- ^ a b c d e Glansdorff, P., Prigogine, I. (1971). Thermodynamic Theory of Structure, Stability and Fluctuations, Wiley-Interscience, London. ISBN 0471302805

- ^ Lebon, G., Jou, J., Casas-Vásquez (2008). Understanding Non-equilibrium Thermodynamics. Foundations, Applications, Frontiers, Springer, Berlin, ISBN 978-3540-74251-7.

- ^ Šilhavý, M. (1997). The Mechanics and Thermodynamics of Continuous Media, Springer, Berlin, ISBN 3-540-58378-5, page 209.

- ^ Grandy, W.T., Jr (2004). Time evolution in macroscopic systems. I: Equations of motion. Found. Phys. 34: 1-20. See [1].

- ^ Grandy, W.T., Jr (2004). Time evolution in macroscopic systems. II: The entropy. Found. Phys. 34: 21-57. See [2].

- ^ Grandy, W.T., Jr (2004). Time evolution in macroscopic systems. III: Selected applications. Found. Phys. 34: 771-813. See [3].

- ^ Grandy 2004 see also [4].

- ^ Jaynes, E.T. (1957). Information theory and statistical mechanics, Physical Review 106: 620-630.

- ^ Jaynes, E.T. (1957). Information theory and statistical mechanics. II, Physical Review 108: 171-190.

- ^ Jaynes, E.T. (1985). Macroscopic prediction, in Complex Systems - Operational Approaches in Neurobiology, edited by H. Haken, Springer-Verlag, Berlin, pp. 254-269, ISBN 3540159231.

- ^ a b Jaynes, E.T. (1965). Gibbs vs Boltzmann Entropies, American Journal of Physics 33: 391-398.

- ^ Evans, D.J., Searles, D.J. (2002). The fluctuation theorem, Advances in Physics 51: 1529-1585

- ^ Wang, G.M., Sevick, E.M., Mittag, E., Searles, D.J., Evans, D.J. (2002) Experimental demonstration of violations of the Second Law of Thermodynamics for small systems and short time scales, Physical Review Letters 89: 050601-1 - 050601-4.

- ^ a b Dewar, R.C. (2005). Maximum entropy production and non-equilibrium statistical mechanics, pp. 41-55 in Non-equilibrium Thermodynamics and the Production of Entropy, edited by A. Kleidon, R.D. Lorenz, Springer, Berlin. ISBN 3540224955.

- ^ Jaynes, E.T. (1963). pp. 181-218 in Brandeis Summer Institute 1962, Statistical Physics, edited by K.W. Ford, Benjamin, New York.

- ^ Jaynes, E.T. (1988). The evolution of Carnot's Principle, pp. 267-282 in Maximum-entropy and Bayesian methods in science and engineering, edited by G.J. Erickson, C.R. Smith, Kluwer, Dordrecht, volume 1, ISBN 9027727937.

- ^ Jaynes, E.T. (1989). Clearing up mysteries, the original goal, pp. 1-27 in Maximum entropy and Bayesian methods, Kluwer, Dordrecht.

- ^ a b Helmholtz, H. (1868). On discontinuous movements of fluids, Philosophical Magazine series 4, vol. 36: 337-346, translated by F. Guthrie from Monatsbericht der koeniglich preussischen Akademie der Wissenschaften zu Berlin April 1868, page 215 et seq.

- ^ a b Strutt, J.W. (Baron Rayleigh) (1878). On the instability of jets, Proceedings of the London Mathematical Society 10: 4-13.

- ^ a b c Strutt, J.W. (Baron Rayleigh) (1896/1926). Section 357 et seq. The Theory of Sound, Macmillan, London, reprinted by Dover, New York, 1945.

- ^ Thom, R. (1975). Structural Stability and Morphogenesis: An outline of a general theory of models, translated from the French by D.H. Fowler, W.A. Benjamin, Reading Ma, ISBN 0805392793

- ^ Riehl, H., Malkus, J.S. (1958). On the heat balance in the equatorial trough zone, Geophysica 6: 503-538.

- ^ Lindzen, R.S. (1977). Some aspects of convection in meteorology, pp. 128-141 in Problems of Stellar Convection, volume 71 of Lecture Notes in Physics, Springer, Berlin, ISBN 9783540085324.

- ^ Thomson, William (1852 a). "On a Universal Tendency in Nature to the Dissipation of Mechanical Energy" Proceedings of the Royal Society of Edinburgh for April 19, 1852 [This version from Mathematical and Physical Papers, vol. i, art. 59, pp. 511.]

- ^ Thomson, W. (1852 b). On a universal tendency in nature to the dissipation of mechanical energy, Philosophical Magazine 4: 304-306.

- ^ Thompson, W. (1854). On a mechanical theory of thermo-electric currents, Proceedings of the Royal Society of Edinburgh pp. 91-98.

- ^ Helmholtz, H. (1869/1871). Zur Theorie der stationären Ströme in reibenden Flüssigkeiten, Verhandlungen des naturhistorisch-medizinischen Vereins zu Heidelberg, Band V: 1-7. Reprinted in Helmholtz, H. (1882), Wissenschaftliche Abhandlungen, volume 1, Johann Ambrosius Barth, Leipzig, pages 223-230 [5]

- ^ from page 2 of Helmholtz 1869/1871, translated by Wikipedia editor.

- ^ Helmholtz, H. (1878). Ueber galvanische Ströme, verursacht durch Concentrationsunterschiede; Folgeren aus der mechanischen Wärmetheorie, Wiedermann's Annalen der Physik und Chemie 3: 201-216.

- ^ Strutt, J.W. (Baron Rayleigh) (1873). Some theorems relating to vibrations, Proceedings of the London Mathematical Society 4:357-368.

- ^ Strutt, J.W. (Baron Rayleigh) (1916). On convection currents in a horizontal layer of fluids, when the higher temperature is on the under side, The London, Edinburgh, and Dublin Philosophical Magazine series 6, volume 32: 529-546.

- ^ Korteweg, D.J., (1883). On a general theorem of the stability of the motion of a viscous fluid, The London, Edinburgh and Dublin Philosophical Journal of Science 16: 112-118.

- ^ a b Onsager, L. (1931). Reciprocal relations in irreversible processes. II, Physical Review 38: 2265-2279

- ^ Onsager, L., Machlup, S. (1953). Fluctuations and Irreversible Processes, Physical Review 91: 1505-1512.

- ^ Machlup, S., Onsager, L., (1953). Fluctuations and Irreversible Processes. II. Systems with kinetic energy, Physical Review 91: 1512-1515.

- ^ a b Prigogine, I. (1945). Modération et transformations irréversibles des systèmes ouverts, Bulletin de la Classe des Sciences., Académie Royale de Belgique 31: 600-606.

- ^ Prigogine, I. (1947). Étude thermodynamique des Phenomènes Irréversibles, Desoer, Liège.

- ^ a b Casimir, H.B.G. (1945). On Onsager's principle of microscopic reversibility, Reviews of Modern Physics 17:343-350

- ^ Ziman, J.M. (1956). The general variational principle of transport theory, Canadian Journal of Physics 34: 1256-1273.

- ^ T. Inoue (2002). Metallo-Thermo-Mechanics–Application to Quenching. In G. Totten, M. Howes, and T. Inoue (eds.), Handbook of Residual Stress. pp. 296-311, ASM International, Ohio.

- ^ Tuck, Adrian F. (2008) Atmospheric Turbulence: a molecular dynamics perspective, Oxford University Press. ISBN 9780199236534. See page 33.

- ^ a b Paltridge, G.W. (1975). Global dynamics and climate - a system of minimum entropy exchange, Quarterly Journal of the Royal Meteorological Society 101:475-484.

- ^ Paltridge G.W.(2001). A physical basis for a maximum of thermodynamic dissipation of the climate system, Quarterly Journal of the Royal Meteorological Society 127:305-313.[6]

- ^ a b Paltridge, G.W. (1978). The steady-state format of global climate, Quarterly Journal of the Royal Meteorological Society 104: 927-945.

- ^ Paltridge, G.W. (1979). Climate and thermodynamic systems of maximum dissipation, Nature 279:630-631.[7]

- ^ Ozawa, H., Ohmura, A., Lorenz, R.D., Pujol, T. (2003). The Second Law of Thermodynamics and the Global Climate System: A Review of the Maximum Entropy Production Principle, Reviews of Geophysics, 41, 4: 1-24.

- ^ Busse, F.H.(1967). The stability of finite amplitude cellular convection and its relation to an extremum principle, Journal of Fluid Mechanics 30(4): 625-649.

- ^ Nicolis, G., Nicolis, C. (1980). On the entropy balance of the earth-atmosphere system, Quarterly Journal of the Royal Meteorological Society 125:1859-1878.